What do billionaires eat for breakfast?

Andrew Ross Sorkin answers all of your questions.

Good morning everyone.

Did anyone see me on TBPN last week? I discussed why I’d buy Carl Icahn’s apartment in Midtown (so I could always take friends to Il Tinello and order Carl Icahn pasta and remind them I live in his old apartment).

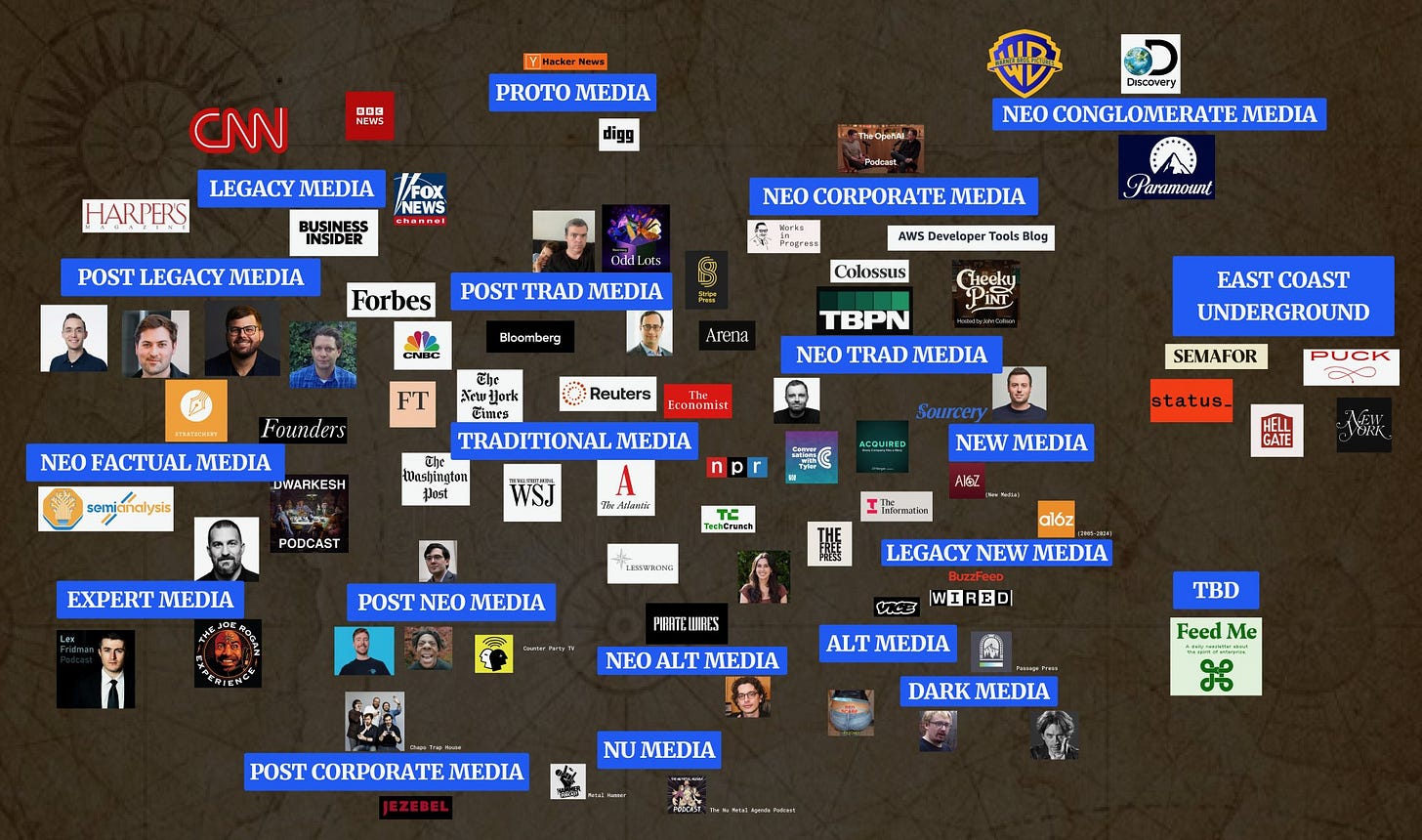

We also discussed this now-viral media map that some people disagreed with, to which I say, take a joke. It was a pleasure to teach the four dozen TBPN interns about what Status, Puck, and Semafor are. Anyway, you can watch it here.

Today’s letter includes: We found out why the SUGARFISH takeout looks different, Andrew Ross Sorkin on whether Derek C. Blasberg should bury his money in a shoebox, the podcast on Patreon making over $180k/month, and why hasn’t Trojan done an ad with Hallie Batchelder yet?

Guest Lecture: Andrew Ross Sorkin

This interview is part of a Feed Me feature called Guest Lecture. In this series, I introduce you all to an expert who I’m curious about, and give paid readers an opportunity to ask them anything they want. Past guests have included Keith McNally, Kareem Rahma, and Audrey Gelman.

Today, Andrew Ross Sorkin answered all of your questions about how he wrote 1929 while balancing his day job, where he’d start his career as a young person in finance, and if there’s a common thread in what billionaires order for breakfast.

“What do you think about the state of the media as someone who works daily to educate readers on complicated issues today? As we see more podcasts, streamers and even TikTokers emerge with points of view, and typically not facts, how do we find truth again?” - Andrea

As someone who cares deeply about facts, what’s fascinating about this moment is that the public is often okay consuming something they know isn’t entirely accurate or is being spun a certain way. They do it knowingly. Everyone has become their own reporter, searching for their own version of truth. That makes fact-based journalism more important than ever — and also more complicated.

“How do you think about keeping DealBook relevant in an era where people are pivoting toward Substacks or podcasts? You’ve interviewed so many leaders, how do you differentiate between the ones who are truly visionaries and those who are just power hungry?” - Yasmine

I started DealBook in 2001 — long before newsletters were even a thing. At the time, we were virtually alone and became a model for others. This was before Politico’s Playbook (2007) or Axios (2016). Substack, which is a terrific technology platform, didn’t arrive until 2017.

I like to think we’ve stayed ahead by understanding our audience at a visceral, human level — what they’re thinking about, what motivates them, what intrigues them. Our focus has always been on reaching the most influential people at the intersection of business and policy — and everyone who wants to understand them better. I still marvel at the names on the subscriber list - many of the people who’ve been on stage at the DealBook Summit read it every morning.

As for visionaries vs power-hungry: They are never black and white. Usually, they are both.

“How would you describe your approach to interviewing? What were some mistakes you made early on in your journalism career?” - Kate

One word: Listen. If you’re prepared and then actually listen to the answers, magic can happen. I learned that lesson at 15. I landed an interview with David Stern, the late NBA commissioner. I had a list of questions written on a yellow legal pad — and I never deviated from it. I don’t think I even heard his answers. When I went home and transcribed the tape (yes, an actual tape recorder), I realized how many follow-ups I’d missed. That moment changed everything for me.

“How did you manage to write such a thick book while carrying out your daily duties for CNBC and The New York Times? How did you design your research process for a period that happened so long ago? And when did you become convinced there was more to tell about the crash of 1929?” - Capital Structure

It wasn’t easy — which probably explains why it took me eight years. It was truly a labor of love. About a decade ago, I became convinced there was an opportunity to write an inside-the-room narrative of 1929 after reading so many great books that tackled the topic through the lens of economists or focused only on certain slices of the story.

I’ve always loved narrative nonfiction like Barbarians at the Gate, Den of Thieves, and Erik Larson’s work. I wasn’t sure if I could find enough rich material to make that kind of story possible — but then I uncovered remarkable transcripts, diaries, and letters. That’s when I knew it could be done.